| ||||

| ||||

| As an ancient civilisation but a young nation that is still in the process of nation building, India faces many threats and challenges to its external and internal security. The foremost among these are the long-festering dispute over Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) with Pakistan and the unresolved territorial and boundary dispute with China. Since its independence from the British on August 15, 1947, India has been forced to fight four wars with Pakistan (1947-48, 1965, 1971 and 1999) and one with China (1962). | ||||

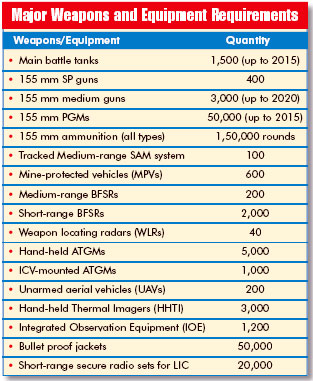

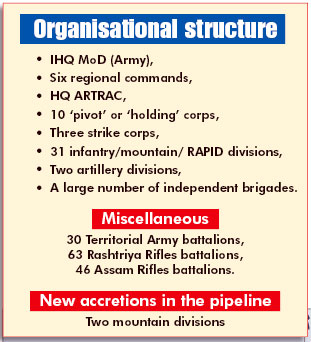

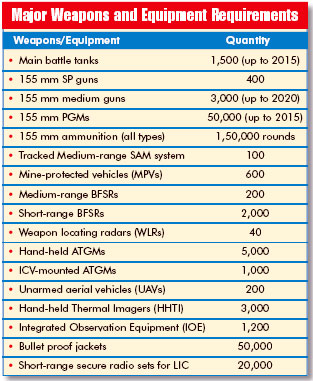

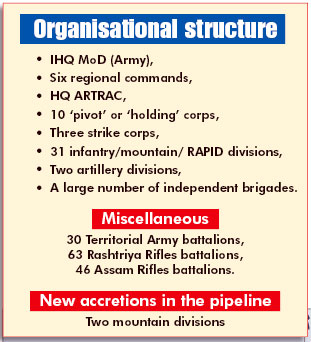

| India's internal security environment has been vitiated by a ‘proxy war’ through which Pakistan has fuelled an uprising in J&K since 1988-89. Various militant movements in India’s north-eastern states and the rising tide of Maoist terrorism in large parts of Central India have also contributed to internal instability. India’s regional security is marked by instability in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Military strength is a pre-requisite for peace and stability on the Indian Sub-continent. India’s socioeconomic development, and that of its neighbours, can continue unhindered only in a secure environment. No nation can afford to be complacent about and to take unmanageable risks with its security. In the rapidly changing geo-strategic environment, comprehensive national strength hinges around modern armed forces that strive constantly to keep pace with the ongoing technological revolution. The rapidly changing nature of warfare, the existential threat from India’s nuclear-armed military adversaries and new threats like terrorism spawned by radical extremism, require a quantum jump in the Indian army’s operational capabilities.  Despite all the tensions confronting it, India has maintained its coherence and its GDP is now growing at an annual rate in excess of eight per cent, except for the dip suffered during the financial crisis. Growth at such a rapid rate would not have been possible but for the sustained vigilance maintained by the Indian armed forces and their many sacrifices in the service of the nation over the last six decades. The Indian army has fulfilled its multifarious roles with admirable valour and in a spirit of sacrifice and selfless devotion to duty. Despite all the tensions confronting it, India has maintained its coherence and its GDP is now growing at an annual rate in excess of eight per cent, except for the dip suffered during the financial crisis. Growth at such a rapid rate would not have been possible but for the sustained vigilance maintained by the Indian armed forces and their many sacrifices in the service of the nation over the last six decades. The Indian army has fulfilled its multifarious roles with admirable valour and in a spirit of sacrifice and selfless devotion to duty. The Indian army ’s personnel strength is approximately 1.1 million. It has performed remarkably well to keep the nation together. It is a firstrate army but has been saddled for long with second-rate weapons and equipment, despite heavy operational commitments on border management and in counter-insurgency operations. The modernisation dilemma that the Indian army faces is that it can carry out substantive modernisation only by simultaneously undertaking large-scale downsizing as the funds available for modernisation are extremely limited. However, it cannot afford to downsize as its operational commitments on border management and internal security duties require a large number of manpower-heavy infantry battalions. In order to successfully defeat future threats and challenges, the Army must modernise its weapons and equipment and upgrade its combat potential by an order of magnitude. The shape and size of the Indian Army’s force structure a few decades hence merits detailed deliberation and quick decisions as capabilities take several decades to create, test and experiment with till they finally mature. It has been well said that there are no prizes for the runners up in war . War is a gruesome affair and, as Napoleon put it so eloquently about two centuries ago, “God is on the side of the battalions with the bigger cannon.” To afford the “bigger cannon” there is a need to make adequate budgetary provisions. The present defence budget, which is pegged at less than 2.0 per cent of India’s GDP, is grossly inadequate to support genuine modernisation as against the replacement of obsolete equipment.  MODERNISATION IMPERATIVES MODERNISATION IMPERATIVESCommand and control systems should be automated and synchronised with the sensors and shooters to exploit the synergies provided by network centric effects based operations. Rapid reaction and air assault capabilities need to be developed to intervene militarily in India’s strategic neighbourhood whenever the national interest so requires. It has to be so as terrorist and militant attacks are often launched and supported from across the borders. The Army’s internal security, counter-insurgency and counterterrorism capabilities also need to be modernised as most of the emerging challenges will lie in the domain of sub-conventional conflict and operations other than war. The time has come to seriously consider a ‘third force’ for internal security operations. Doctrinal concepts, organisations structures and training methodologies must keep pace with technological advancements. The Army must train its personnel for certainty and educate them for uncertainty. Restructuring and modernising the Indian Army will require political courage, military astuteness, a nonparochial approach and a singularity of purpose. NEED FOR A NATIONAL MILITARY COMMISSION  Only a future-ready army can march into the coming decades with confidence, well prepared to tackle the new challenges looming over the horizon. The Government of India must appoint a bipartisan National Military Commission to go into the whole gamut of restructuring and modernisation. The commission should comprise eminent political leaders, armed forces veterans, civilian administrators, diplomats and scholars who are capable of dispassionate reasoning and are familiar with the current military discourse. It should be given no more than six months to complete its work so that the restructuring exercise can begin early and be completed by 2020-25. Only a future-ready army can march into the coming decades with confidence, well prepared to tackle the new challenges looming over the horizon. The Government of India must appoint a bipartisan National Military Commission to go into the whole gamut of restructuring and modernisation. The commission should comprise eminent political leaders, armed forces veterans, civilian administrators, diplomats and scholars who are capable of dispassionate reasoning and are familiar with the current military discourse. It should be given no more than six months to complete its work so that the restructuring exercise can begin early and be completed by 2020-25. MODERNISATION PROGRAMMES Sadly, the Indian Army has almost completely missed the ongoing Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA).This is because extremely limited funds are made available for modernisation and a large portion of the funds allotted on the capital account is surrendered year after year due to political scandals and bureaucratic red tape. Defence Minister A K Antony had admitted recently, “New procurements have commenced… but we are still lagging by 15 years.” If this state of affairs continues much longer, the quantitative military gap with China will soon become a qualitative gap as well. Also, the slender conventional edge that the Indian army enjoys over its Pakistani counterpart will be eroded further as Pakistan is spending considerably large sums of money on its military modernisation. While Pakistan has acquired 320 T-80 UD tanks and is on course to add Al Khalid tanks that it has codeveloped with China to its armour fleet, vintage Vijayant tanks and the ageing T-55s continue in the Indian Army’s inventory despite their obsolescence. The indigenously developed Arjun MBT has not quite met the Army’s expectations due to recurring technological problems and cost over-runs, though the tank has entered serial production to equip two regiments. Consequently, 310 T-90S MBTs had to be imported from Russia. In December 2007, a contract was signed for an additional 347 T-90 tanks to be assembled in India. Meanwhile, a programme has been launched to modernise the Sovietvintage T-72 M1 Ajeya MBTs that have been the mainstay of the army’s Strike Corps and their armoured divisions since the 1980s. The programme seeks to upgrade the night fighting capabilities and fire control system of the tank, among other modifications. Approximately 1,700 T-72 M1s have been manufactured under licence at the Heavy Vehicle Factory (HVF), Avadi. The BMP-1 and, to a lesser extent, the BMP-2 infantry combat vehicles, which have been the mainstay of the mechanised infantry battalions for long, are now ageing and replacements need to be found soon.  The replacement vehicles must be capable of being successfully employed for internals security duties and counter-insurgency operations in addition to their primary role in conventional conflict. The replacement vehicles must be capable of being successfully employed for internals security duties and counter-insurgency operations in addition to their primary role in conventional conflict. Despite the lessons learnt during the Kargil conflict of 1999, where artillery firepower had undeniably paved the way for victory, modernisation of the artillery continues to lag behind. The last major acquisition of towed gun-howitzers was that of about 400 pieces of 39-calibre 155 mm FH-77B howitzers from Bofors of Sweden in the mid-1980s. New tenders have been floated for 155mm/ 39- calibre light weight howitzers for the mountains and 155mm/52-calibre long-range howitzers for the plains, as well as for self-propelled guns for the desert terrain. As re-trials have not yet commenced, it will take almost five years more for the first of the new guns to enter service. The artillery also needs large quantities of precision guided munitions (PGMs) for more accurate targeting in future battles. The present stocking levels are rather low. A contract for the acquisition of two regiments of the 12-tube, 300 mm Smerch multi-barrel rocket launcher (MBRL) system with 90 km range was signed with Russia’s Rosoboronexport in early-2006. The BrahMos supersonic cruise missile (Mach 2.8 to 3.0), with a precision strike capability, very high kill energy and maximum range of 290 km, was inducted into the army in July 2007. These terrain hugging missiles are virtually immune to counter measures due to their high speed and very low radar cross section. Both of these will provide a major boost for hitting the enemy at long ranges.  The indigenously designed and manufactured Pinaka multi-barrel rocket system is likely to enter service in the near future. It is also time to now consider the induction of unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) armed with air-to-surface missiles into service for air-to-ground precision attacks. The indigenously designed and manufactured Pinaka multi-barrel rocket system is likely to enter service in the near future. It is also time to now consider the induction of unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) armed with air-to-surface missiles into service for air-to-ground precision attacks. The Corps of army Air Defence is also faced with serious problems of obsolescence. The vintage L-70 40 mm AD gun system, the four-barrelled ZSU-23-4 Schilka (SP) AD gun system, the SAM-6 (Kvadrat) and the SAM-8 OSA-AK have all seen better days and need to be urgently replaced by more responsive modern AD systems that are capable of defeating current and future threats. The Akash and Trishul surfaceto- air missiles have not yet been fully developed by India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), which is tasked to build indigenous capabilities. The short-range and medium-range SAM acquisition programmes are embroiled in red tape. This is one area where the Army has lagged behind seriously in its modernisation efforts. The modernisation plans of India’s cutting edge infantry battalions, aimed at enhancing their capability for surveillance and target acquisition at night and boosting their firepower for precise retaliation against infiltrating columns and terrorists holed up in built-up areas, are moving forward but at a snail’s pace. These include plans to acquire hand-held battlefield surveillance radars (BFSRs), and hand-held thermal imaging devices (HHTIs) for observation at night. Standalone infra-red, seismic and acoustic sensors need to be acquired in large numbers to enable infantrymen to dominate the Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan and detect infiltration of Pakistan-sponsored terrorists. Details are important. For instance, it is important to ensure that powering devices for hand-held and manportable systems are powered by the best-available batteries and energy devices that last long. Similarly, the operational capabilities of Army aviation, engineers, signal communications, reconnaissance, surveillance and target acquisition (RSTA) branches need to be substantially enhanced so that the overall combat potential of the army can be improved by an order of magnitude. Modern strategic and tactical level command and control systems need to be acquired on priority basis for better synergies during conventional and sub-conventional conflict. While the Artillery Combat Command and Control system (ACCC&S) has entered service, the Battlefield Surveillance System (BSS) is yet to mature. The communication systems linking these C3I systems, Project ASTROIDS and the Tactical Communication System (TCS), are still in various stages of development. Despite being the largest user of space, the Indian Army does not have a dedicated military satellite to bank on. CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS With India’s defence budget now pegged at less than 2.0 per cent of the GDP, the funds available for modernisation of the armed forces are grossly inadequate. The only other alternative of undertaking quantitative reduction in force levels so as to save funds for modernisation cannot be resorted to due to large-scale manpowerintensive operational commitments of the Army. The Army is not only deployed along or stationed close to a long border with China and along the LoC with Pakistan on a permanent basis but is also engaged extensively in manpower-intensive counter-insurgency operations and, hence, finds it difficult to reduce its manpower. As the availability of funds remains low, India’s military modernisation is likely to continue at a slow pace in the foreseeable future. Finally, the Indian Army of the future must be light, lethal and wired; ready to fight and win India’s future wars jointly with the Indian Navy and Indian Air Force over the full spectrum of conflict, from sub-conventional conflict and operations other than war to an all-out conventional war; so as to ensure regional stability and internal security. The nation must get a modern force that can fight and win India’s future battles with the least number of casualties and minimum collateral damage through surgical strikes. The Indian Army should be a force capable of carrying the battle into an enemy territory, from where terror or military attacks are launched or might originate. Only then will the nation get a peaceful environment for socioeconomic development. The aim should be to ensure peace through conventional deterrence so that India can achieve all round prosperity and join the ranks of the world’s developed nations.  The author is Director, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi. | ||||

| © India Strategic |

Indian Army Modernisation Needs a Major Push

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

Indian Army Modernisation Needs a Major Push

| ||||

| ||||

| As an ancient civilisation but a young nation that is still in the process of nation building, India faces many threats and challenges to its external and internal security. The foremost among these are the long-festering dispute over Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) with Pakistan and the unresolved territorial and boundary dispute with China. Since its independence from the British on August 15, 1947, India has been forced to fight four wars with Pakistan (1947-48, 1965, 1971 and 1999) and one with China (1962). | ||||

| India's internal security environment has been vitiated by a ‘proxy war’ through which Pakistan has fuelled an uprising in J&K since 1988-89. Various militant movements in India’s north-eastern states and the rising tide of Maoist terrorism in large parts of Central India have also contributed to internal instability. India’s regional security is marked by instability in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Military strength is a pre-requisite for peace and stability on the Indian Sub-continent. India’s socioeconomic development, and that of its neighbours, can continue unhindered only in a secure environment. No nation can afford to be complacent about and to take unmanageable risks with its security. In the rapidly changing geo-strategic environment, comprehensive national strength hinges around modern armed forces that strive constantly to keep pace with the ongoing technological revolution. The rapidly changing nature of warfare, the existential threat from India’s nuclear-armed military adversaries and new threats like terrorism spawned by radical extremism, require a quantum jump in the Indian army’s operational capabilities.  Despite all the tensions confronting it, India has maintained its coherence and its GDP is now growing at an annual rate in excess of eight per cent, except for the dip suffered during the financial crisis. Growth at such a rapid rate would not have been possible but for the sustained vigilance maintained by the Indian armed forces and their many sacrifices in the service of the nation over the last six decades. The Indian army has fulfilled its multifarious roles with admirable valour and in a spirit of sacrifice and selfless devotion to duty. Despite all the tensions confronting it, India has maintained its coherence and its GDP is now growing at an annual rate in excess of eight per cent, except for the dip suffered during the financial crisis. Growth at such a rapid rate would not have been possible but for the sustained vigilance maintained by the Indian armed forces and their many sacrifices in the service of the nation over the last six decades. The Indian army has fulfilled its multifarious roles with admirable valour and in a spirit of sacrifice and selfless devotion to duty. The Indian army ’s personnel strength is approximately 1.1 million. It has performed remarkably well to keep the nation together. It is a firstrate army but has been saddled for long with second-rate weapons and equipment, despite heavy operational commitments on border management and in counter-insurgency operations. The modernisation dilemma that the Indian army faces is that it can carry out substantive modernisation only by simultaneously undertaking large-scale downsizing as the funds available for modernisation are extremely limited. However, it cannot afford to downsize as its operational commitments on border management and internal security duties require a large number of manpower-heavy infantry battalions. In order to successfully defeat future threats and challenges, the Army must modernise its weapons and equipment and upgrade its combat potential by an order of magnitude. The shape and size of the Indian Army’s force structure a few decades hence merits detailed deliberation and quick decisions as capabilities take several decades to create, test and experiment with till they finally mature. It has been well said that there are no prizes for the runners up in war . War is a gruesome affair and, as Napoleon put it so eloquently about two centuries ago, “God is on the side of the battalions with the bigger cannon.” To afford the “bigger cannon” there is a need to make adequate budgetary provisions. The present defence budget, which is pegged at less than 2.0 per cent of India’s GDP, is grossly inadequate to support genuine modernisation as against the replacement of obsolete equipment.  MODERNISATION IMPERATIVES MODERNISATION IMPERATIVESCommand and control systems should be automated and synchronised with the sensors and shooters to exploit the synergies provided by network centric effects based operations. Rapid reaction and air assault capabilities need to be developed to intervene militarily in India’s strategic neighbourhood whenever the national interest so requires. It has to be so as terrorist and militant attacks are often launched and supported from across the borders. The Army’s internal security, counter-insurgency and counterterrorism capabilities also need to be modernised as most of the emerging challenges will lie in the domain of sub-conventional conflict and operations other than war. The time has come to seriously consider a ‘third force’ for internal security operations. Doctrinal concepts, organisations structures and training methodologies must keep pace with technological advancements. The Army must train its personnel for certainty and educate them for uncertainty. Restructuring and modernising the Indian Army will require political courage, military astuteness, a nonparochial approach and a singularity of purpose. NEED FOR A NATIONAL MILITARY COMMISSION  Only a future-ready army can march into the coming decades with confidence, well prepared to tackle the new challenges looming over the horizon. The Government of India must appoint a bipartisan National Military Commission to go into the whole gamut of restructuring and modernisation. The commission should comprise eminent political leaders, armed forces veterans, civilian administrators, diplomats and scholars who are capable of dispassionate reasoning and are familiar with the current military discourse. It should be given no more than six months to complete its work so that the restructuring exercise can begin early and be completed by 2020-25. Only a future-ready army can march into the coming decades with confidence, well prepared to tackle the new challenges looming over the horizon. The Government of India must appoint a bipartisan National Military Commission to go into the whole gamut of restructuring and modernisation. The commission should comprise eminent political leaders, armed forces veterans, civilian administrators, diplomats and scholars who are capable of dispassionate reasoning and are familiar with the current military discourse. It should be given no more than six months to complete its work so that the restructuring exercise can begin early and be completed by 2020-25. MODERNISATION PROGRAMMES Sadly, the Indian Army has almost completely missed the ongoing Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA).This is because extremely limited funds are made available for modernisation and a large portion of the funds allotted on the capital account is surrendered year after year due to political scandals and bureaucratic red tape. Defence Minister A K Antony had admitted recently, “New procurements have commenced… but we are still lagging by 15 years.” If this state of affairs continues much longer, the quantitative military gap with China will soon become a qualitative gap as well. Also, the slender conventional edge that the Indian army enjoys over its Pakistani counterpart will be eroded further as Pakistan is spending considerably large sums of money on its military modernisation. While Pakistan has acquired 320 T-80 UD tanks and is on course to add Al Khalid tanks that it has codeveloped with China to its armour fleet, vintage Vijayant tanks and the ageing T-55s continue in the Indian Army’s inventory despite their obsolescence. The indigenously developed Arjun MBT has not quite met the Army’s expectations due to recurring technological problems and cost over-runs, though the tank has entered serial production to equip two regiments. Consequently, 310 T-90S MBTs had to be imported from Russia. In December 2007, a contract was signed for an additional 347 T-90 tanks to be assembled in India. Meanwhile, a programme has been launched to modernise the Sovietvintage T-72 M1 Ajeya MBTs that have been the mainstay of the army’s Strike Corps and their armoured divisions since the 1980s. The programme seeks to upgrade the night fighting capabilities and fire control system of the tank, among other modifications. Approximately 1,700 T-72 M1s have been manufactured under licence at the Heavy Vehicle Factory (HVF), Avadi. The BMP-1 and, to a lesser extent, the BMP-2 infantry combat vehicles, which have been the mainstay of the mechanised infantry battalions for long, are now ageing and replacements need to be found soon.  The replacement vehicles must be capable of being successfully employed for internals security duties and counter-insurgency operations in addition to their primary role in conventional conflict. The replacement vehicles must be capable of being successfully employed for internals security duties and counter-insurgency operations in addition to their primary role in conventional conflict. Despite the lessons learnt during the Kargil conflict of 1999, where artillery firepower had undeniably paved the way for victory, modernisation of the artillery continues to lag behind. The last major acquisition of towed gun-howitzers was that of about 400 pieces of 39-calibre 155 mm FH-77B howitzers from Bofors of Sweden in the mid-1980s. New tenders have been floated for 155mm/ 39- calibre light weight howitzers for the mountains and 155mm/52-calibre long-range howitzers for the plains, as well as for self-propelled guns for the desert terrain. As re-trials have not yet commenced, it will take almost five years more for the first of the new guns to enter service. The artillery also needs large quantities of precision guided munitions (PGMs) for more accurate targeting in future battles. The present stocking levels are rather low. A contract for the acquisition of two regiments of the 12-tube, 300 mm Smerch multi-barrel rocket launcher (MBRL) system with 90 km range was signed with Russia’s Rosoboronexport in early-2006. The BrahMos supersonic cruise missile (Mach 2.8 to 3.0), with a precision strike capability, very high kill energy and maximum range of 290 km, was inducted into the army in July 2007. These terrain hugging missiles are virtually immune to counter measures due to their high speed and very low radar cross section. Both of these will provide a major boost for hitting the enemy at long ranges.  The indigenously designed and manufactured Pinaka multi-barrel rocket system is likely to enter service in the near future. It is also time to now consider the induction of unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) armed with air-to-surface missiles into service for air-to-ground precision attacks. The indigenously designed and manufactured Pinaka multi-barrel rocket system is likely to enter service in the near future. It is also time to now consider the induction of unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) armed with air-to-surface missiles into service for air-to-ground precision attacks. The Corps of army Air Defence is also faced with serious problems of obsolescence. The vintage L-70 40 mm AD gun system, the four-barrelled ZSU-23-4 Schilka (SP) AD gun system, the SAM-6 (Kvadrat) and the SAM-8 OSA-AK have all seen better days and need to be urgently replaced by more responsive modern AD systems that are capable of defeating current and future threats. The Akash and Trishul surfaceto- air missiles have not yet been fully developed by India’s Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), which is tasked to build indigenous capabilities. The short-range and medium-range SAM acquisition programmes are embroiled in red tape. This is one area where the Army has lagged behind seriously in its modernisation efforts. The modernisation plans of India’s cutting edge infantry battalions, aimed at enhancing their capability for surveillance and target acquisition at night and boosting their firepower for precise retaliation against infiltrating columns and terrorists holed up in built-up areas, are moving forward but at a snail’s pace. These include plans to acquire hand-held battlefield surveillance radars (BFSRs), and hand-held thermal imaging devices (HHTIs) for observation at night. Standalone infra-red, seismic and acoustic sensors need to be acquired in large numbers to enable infantrymen to dominate the Line of Control (LoC) with Pakistan and detect infiltration of Pakistan-sponsored terrorists. Details are important. For instance, it is important to ensure that powering devices for hand-held and manportable systems are powered by the best-available batteries and energy devices that last long. Similarly, the operational capabilities of Army aviation, engineers, signal communications, reconnaissance, surveillance and target acquisition (RSTA) branches need to be substantially enhanced so that the overall combat potential of the army can be improved by an order of magnitude. Modern strategic and tactical level command and control systems need to be acquired on priority basis for better synergies during conventional and sub-conventional conflict. While the Artillery Combat Command and Control system (ACCC&S) has entered service, the Battlefield Surveillance System (BSS) is yet to mature. The communication systems linking these C3I systems, Project ASTROIDS and the Tactical Communication System (TCS), are still in various stages of development. Despite being the largest user of space, the Indian Army does not have a dedicated military satellite to bank on. CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS With India’s defence budget now pegged at less than 2.0 per cent of the GDP, the funds available for modernisation of the armed forces are grossly inadequate. The only other alternative of undertaking quantitative reduction in force levels so as to save funds for modernisation cannot be resorted to due to large-scale manpowerintensive operational commitments of the Army. The Army is not only deployed along or stationed close to a long border with China and along the LoC with Pakistan on a permanent basis but is also engaged extensively in manpower-intensive counter-insurgency operations and, hence, finds it difficult to reduce its manpower. As the availability of funds remains low, India’s military modernisation is likely to continue at a slow pace in the foreseeable future. Finally, the Indian Army of the future must be light, lethal and wired; ready to fight and win India’s future wars jointly with the Indian Navy and Indian Air Force over the full spectrum of conflict, from sub-conventional conflict and operations other than war to an all-out conventional war; so as to ensure regional stability and internal security. The nation must get a modern force that can fight and win India’s future battles with the least number of casualties and minimum collateral damage through surgical strikes. The Indian Army should be a force capable of carrying the battle into an enemy territory, from where terror or military attacks are launched or might originate. Only then will the nation get a peaceful environment for socioeconomic development. The aim should be to ensure peace through conventional deterrence so that India can achieve all round prosperity and join the ranks of the world’s developed nations.  The author is Director, Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS), New Delhi. | ||||

| © India Strategic |

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment